I’m definitely a “morning person.” I’ve often written here of my love of mornings. I enjoy being around (and conscious) for the rising of the sun; more so in the summers, when it rises in the five o’clock hour. I love the quiet. It’s like I’ve got the world to myself for a while.

Most mornings, I don’t have much time before I have to get off to work. I’m almost always in the office by seven, and get so much done when I’m uninterrupted and fresh for the day. Weekends are different. In the months during which biking is a practical possibility, I’m up early on Saturday to hit the road before sunrise and get home by noon. Saturday mornings get rough though when the weather (i.e. cold, icy conditions) prevents me from getting out. I hate being thrown off my routine.

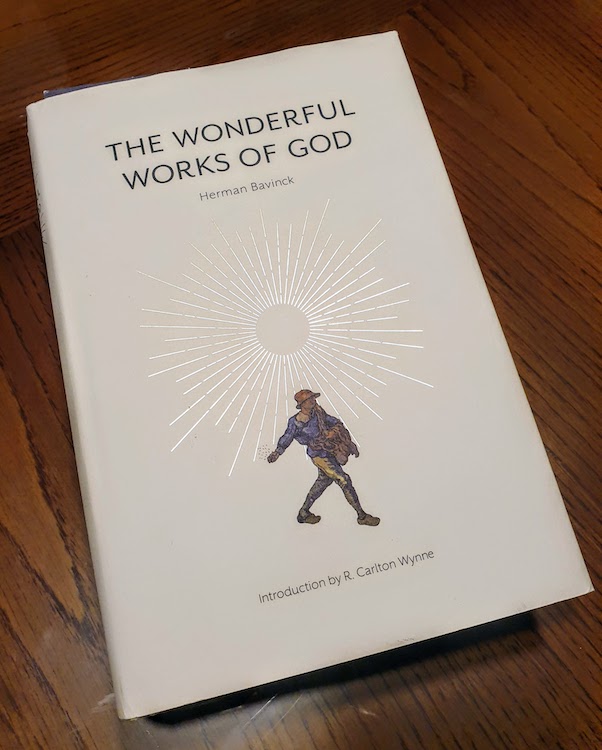

Sundays, though, have always been mornings for quiet reflection and reading. I like to put aside the things I handle through the week just to rest in God for a while. So instead of picking up a Pulitzer Prize-winner, I’ll grab a book like The Wonderful Works of God by Herman Bavinck and do my reading out of that. It’s such a wonderful book, written over a century ago, but so well. I’m really enjoying it.

Today, I finished the chapter on “The Holy Scriptures,” in which he walked me through the background and purpose of each genre within the Bible. This is generally old news to me. Having read the Bible through dozens of times, I get the overall feel and understanding of each book within the whole. But Bavinck brings a certain freshness and logic in his explanations that, to me, are really enjoyable. I love his perspective on the construction of the first books of the Bible, generally by Moses, but inclusive of oral tradition, earlier writings, and later revisions. Here are a couple of excerpts:

“Hence it is quite possible that various portions of the five books of Moses were in part extant before his time, and also that they were revised by Moses himself, or by others at Moses’ behest, or that, later on, after Moses’ death, some of them were edited in his spirit and manner, and added to the already extant portions [the account of Moses’ death, for example, could not have been written by Moses].”

…

“This is to take nothing away from the Divine authority of the Word, and is a possibility which is not at all contradicted by the recurrent Scriptural expression: the law, or the book of Moses. For the five books of Moses remain the book or the law of Moses even though some parts were derived by him from other sources, were set down at his behest by his officers, or were edited in his spirit by those who came after. Paul too did not as a general rule write his letters himself, but had them written by another hand (1 Cor. 16:21). And the book of Psalms is sometimes ascribed in its entirety to David because he is the founder of psalmody, and this is done even though a number of the Psalms are not those of David but are of other authors.”

Herman Bavinck, The Wonderful Works of God, p. 88-89

This is important, because at times the veracity of the Bible is attacked because of attribution of authorship. Claims like, “Well, you know, Moses didn’t really write the Pentateuch,” and “Paul didn’t write Hebrews” are presented as if they contradict the whole of the Bible. We know who wrote the Bible – men, by the inspiration of God. Unfortunately, too many people stop at the word “men” and leave God out of it entirely. This is a foolish perspective, as you cannot fall upon the sovereignty of a God whose definition rests wholly on the opinions, whims, and errors of unguided authors. There should be no guessing game when it comes to the God in whom one believes as the sole source of their eternal salvation.

But Bavinck does a pleasant job of walking us through this. Of explaining those objections to various perspectives of scripture which are thrown out there as shortcomings that discredit the whole of it. He focuses on the foundation of it all – that the ultimate author is God, who, by the work of his Holy Spirit, used men to write his words in their own way, using their own voices. But God’s Word nonetheless. I’m happy for that – that I don’t have to rely on myself to make up a God that supposedly runs the whole world. That I can turn to what he says and, through deep, diligent, and honest study, can touch a portion of his truth – the portion that he means for us to understand.

All good stuff.

The question is, then, “when?” When should a person know this? When should a Christian read the likes of Bavinck. Or Boice. Or Grudem. I’m well-read in Christian theology and literature, and I find most of what Bavinck has said so far (three chapters in) touches on things that I already know. But he brings clarity. In today’s case, I’ve long known the arguments of authorship, but Bavinck captures the explanations in ways that helped me articulate my thoughts. So I wonder, should I have read Bavinck from the start to clear up questions? And this can also lead to the question, “when should I recommend Bavinck to others?” It’s obvious that one should first know what the books of Moses are before being told the scholastic debates on their actual authorship. And even then, it might only benefit someone with a heart for apologetics to even care who actually wrote all of the books of the Bible.

Still, I must remember this – the attacks will come, and sometimes the blows land (though their sting softens as we mature in our faith). But the adversity should strengthen our faith rather than demolish it.

I’m reminded of a conversation with a friend quite early in my Christian life. While I maintained that God was able to do all things, she asked, “Can he learn?” Perhaps she thought it was her “go-to gotcha,” but rather than make me question my faith, she instead had me wondering how I could answer such a question – and that’s a good thing. She led me to deeper faith by eventually letting me discover deeper truths and not just happy Christian platitudes. I needed to dig more to find out that even the Bible tells us God cannot do all things (he cannot lie, for example), but rather, God can do all things that are within his character and the realm of logical possibility.

So the answer to the question, “When should a Christian read the likes of Bavinck?” should be “It depends.” But if I were to pin down a time, I’d say sometime after the dust has settled in a person’s understanding of the basics. This information would have been very useful to me earlier on in my life, but only really to solidify what I was learning. In any case, it cannot hurt to read good theology, but even better under the guidance of someone who can answer questions, and, of course, grow with the questioner.