I’ve never been one to break down the deep meaning of classic written works. I’m simply a, “I like what I see” kind of guy. So my tastes in writers was nearly non-existent in my earlier years. There just wasn’t a lot to like in my eyes.

But things started to catch on over time, and the accidental find of The Expedition of Humphry Clinker turned a corner for me. I was able to read the book and just be amazed at Smollett’s way with words. I’ve written about it before — long, drawn out sentences. Multiple styles within the story (Clinker is an epistolary novel — the story is told entirely through letters written by the characters). Misspellings and poor grammar. And hilarious! But I guess you have to have a bit of a weird way of looking at things to get it.

And, as I’ve written here before, I love the work of Salman Rushdie. There’s depth there, even if it seems long-winded to some (my sister Joan, mainly). I loved Midnight’s Children, the work originally recommended to me by a friend, but even before that, and when searching for that book in the library, I stumbled upon Two Years Eight Months and Twenty-Eight Nights, and was absolutely fascinated.

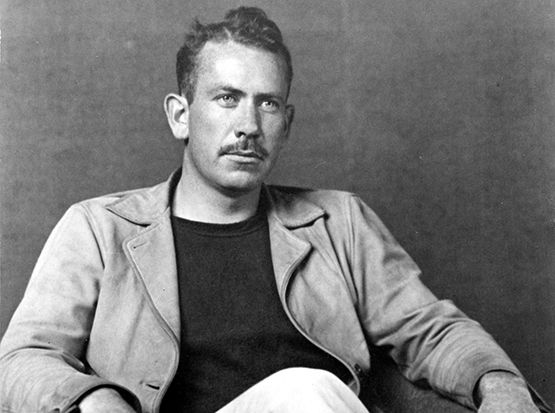

And of course I’ve discovered so late in life, John Steinbeck. As I mentioned before, I’m reading The Log From the Sea of Cortez, a work of non-fiction about collecting marine life in the Gulf of California with his friend, Doc Ricketts, and he makes even that so worthwhile. I just had to laugh at this (long) passage about the bureaucracy of dealing with diplomats to get clearance to do this work:

It was not likely that we could explain our job to the satisfaction of a soldier. It would seem ridiculous to the military mind to travel fifteen hundred mils for the purpose of turning over rocks on the seashore and picking up small animals, very few of which were edible; and doing all this without shooting at anyone. Besides, our equipment might have looked subversive to one who had seen the war sections of Life and Pic and Look. We carried no firearms except a .22-caliber pistol and a very rusty ten-gauge shotgun. But an oxygen cylinder might look too much like a torpedo to an excitable rural soldier, and some of the laboratory equipment could have had a lethal look about it. We were not afraid for ourselves, but we imagined being held in some mud cuartel while the good low tides went on and we missed them. In our naïveté, we considered that our State Department, having much business with the Mexican government, might include a paragraph about us in one of its letters, which would convince Mexico of our decent intentions. To his end, we wrote to the State Department explaining our project and giving a list of people who would confirm the purity of out motives. Then we waited in childlike faith that when a thing is stated simply and evidence of its truth is included there need be no mix-up. Besides, we told ourselves, we were American citizens and the government was our servant. Alas, we did not know diplomatic procedure. In due course, we had an answer from the State Department. In language so diplomatic as to be barely intelligible it gently disabused us. In the first place, the State Department was not our servant, however other departments might feel about it. The State Department had little or no interest in the collection of marine invertebrates unless carried on by an institution of learning, preferably with Dr. Butler as its president. The government never made such representations for private citizens. Lastly, the State Department hoped to God we would not get into trouble and appeal to it for aid. All this was concealed in language so beautiful and incomprehensible that we began to understand why diplomats say they are “studying” a message from Japan or England or Italy. We studied this letter for the better part of one night, reduced its sentences to words, built it up again, and came out with the above-mentioned gist. “Gist” is, we imagine, a word which makes the State Department shudder with its vulgarity.

There we were, with no permits and the imaginary soldier still upset by our oxygen tube. In Mexico, certain good friends worked to get us the permits; the consul-general in San Francisco wrote letters about us, and then finally, through a friend, we got in touch with Mr. Castillo Najera, the Mexican ambassador to Washington. To our wonder there came an immediate reply from the ambassador which said there was no reason why we should not go and that he would see the permits were issued immediately. His letter said just that. There was a little sadness in us when we read it. The Ambassador seemed such a good man we felt it a pity that he had no diplomatic future, that he could never get anywhere in the world of international politics. We understood his letter the first time we read it. Clearly, Mr. Castillo Najera is a misfit and a rebel. He not only wrote clearly, but he kept his word. The permits came through quickly and in order. And we wish here and now to assure this gentleman that whenever the inevitable punishment for his logic and clarity falls upon him we will gladly help him to get a new start in some other profession.

I don’t even think Joan could argue with that (but don’t hold me to that assertion). Maybe the passage just struck me because frustration with government bureaucracy is both universal and long-lived. Steinbeck is writing nearly 75 years ago, and he may as well have been writing yesterday…but even more so.

I’ll always be searching for more good writing. Reading is so incredibly entertaining and rewarding. i would much rather chase good books than good memes. Good books will take me elsewhere while memes generally don’t. And they most often do their work for so much longer periods of time. They capture imaginations and inspire, and then they hold me there, rapt and happy to be wherever they send me.

These days, they seem the only places worth going any more.