My brush with the notorious Chen Doohwan was not a brush at all. It was more of a swing-and-a-miss. Not that I (or anyone else) could take a literal “swing” at the guy without being gunned down, and not that I had a choice in any case. When he came to visit our unit in 1987, I was in my office down the hall and around the corner when he arrived, and once he got to the building, movement inside was locked down (quite literally for me, as my office was located in a small vault). We had to clear the halls and “shelter-in-place” for the duration, which meant I had to sit there in that room the whole time he was there…and then some. Friends of mine who did see him observed that he was a short man, especially compared to his body guards (who were all heavily armed – people wanted Chen dead).

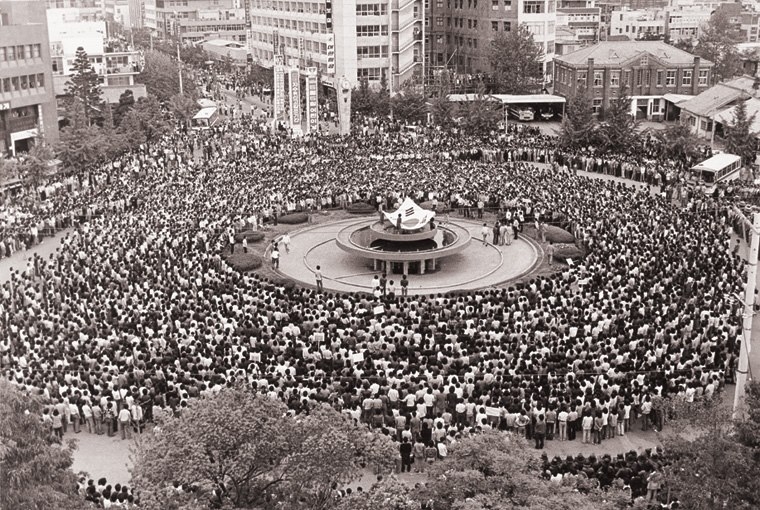

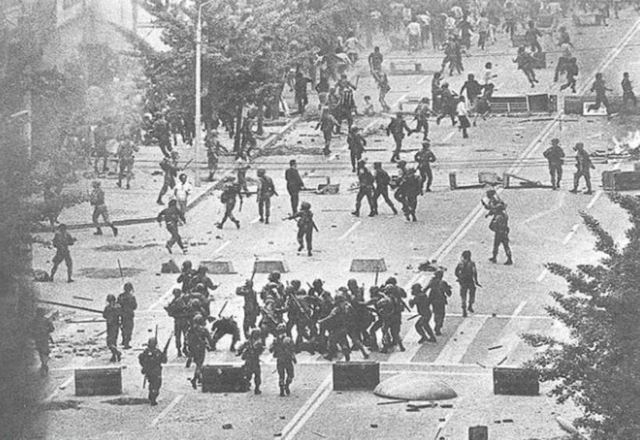

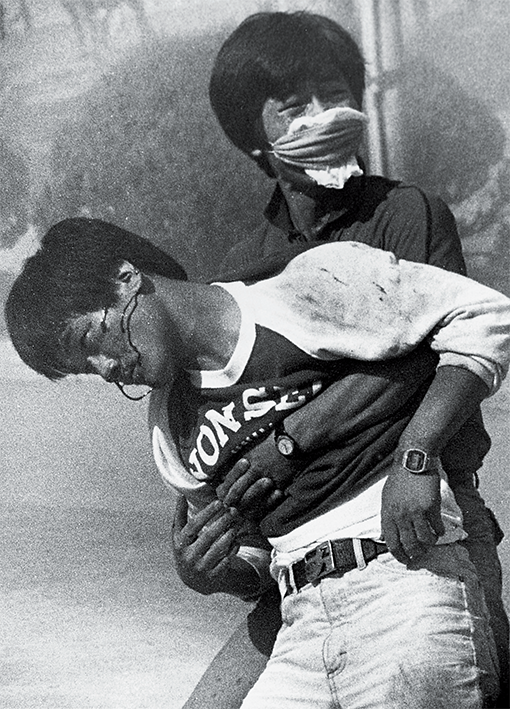

And I must say, people wanting him dead made for an interesting decade (the 80s) here in Korea. Not many people in today’s democracies have had the chance to live under the regime of a strongman dictator. They don’t remember the turmoil of the times; like when the nation was under martial law after President Pak’s assassination in ’79 (I first came to Korea in 1983, two years after it was lifted). They weren’t around when the North attempted to assassinate Chen in Burma, killing several members of his cabinet instead. They weren’t around for, but certainly know about the events in Gwangju, when his soldiers mowed down hundreds (perhaps thousands) of civilian protestors at the beginning of the decade.

On a more positive note though – if you can consider anything about him positive – Chen’s reign in South Korea was the beginning of the end for the tumultuous post-war, fear-driven style of government South Korea employed at the time. It’s another testament to the resiliency of the Korean people and the deep tradition of rising against oppression that they had so famously taken in the past. With the impetus of Chen’s rule, Korea turned the corner from brutal dictatorship to vibrant democracy in just a few short years (with bumps along the way, but still a resounding success).

I think most of history can agree, Chen really did nothing of value for the country (other than driving its citizens to his overthrow). Some may point to the Seoul Olympics in ’88, but considering he was run out of office by the pro-democracy demonstrations in the summer of ’87 (a time when I got to experience the slight effects of wafting tear gas myself), I can’t say that the Olympics were boosting his popularity at the time. He had to go, Olympics or not.

In the end, Chen got to live a long life, and I think that bothers some people. Even though he died from a form of blood cancer, he was already 90. Micha told me that, as a military man, he wanted to be buried by the DMZ. The current president had no comment on that, but I’m sure Chen’s wishes won’t be honored. In one last shot at the man – who remained unrepentant to the end – the president can act on behalf of the thousands, if not tens of thousands of Korea’s citizens who had no such luxury as to choose their final resting places. They’re buried in unmarked graves, or they simply disappeared without a trace during the man’s reign. If it were up to me, not only would burying him at the DMZ be a hard “no,” I’d do something quite the opposite. I’d give his ashes to some low-level office worker and tell him to go dump them somewhere. Anywhere. Just don’t tell anyone where. I might go so far as to not even tell the guy they were Chen’s ashes. Just disappear the guy like he disappeared so many others.

I usually have at least a twinge of sympathy or reminiscence when I hear of someone’s death. I might think back on their lives (as I’m sort of doing now) and try to come up with any of the good that may have come out of it. But not so, here. I was young, free, and ignorant in the Korea of the 80s. Members of the US military were respected by a thankful Korean populace, and we were little affected by the politics of the nation. We got away with a lot of crap back then, and maybe that’s why you might hear old guys pining for “the good old days, when we worked hard and played hard.” But I know those good old days were not so good for the Korean people. And my knowing that now makes all of the difference. When I was a young fool, prevented from seeing the president of the nation by being locked in a vault 34 years ago, I might have been a bit disappointed. Being on the other side of all those years now, I can only feel malice for the man and pride in the Korean people for overcoming his brutality. It really doesn’t take a lot of extra maturity to tip one into that perspective, but it’s certainly something I could’ve used back then.

So I guess all I can give now are my sympathies to the Korean people – not that they’re mourning the guy, but rather that there are still many who feel the pain of his work and who were waiting for an apology that will now never come. I certainly hope that they can finally move on from that dark period in their history. And of course, I still look forward to better things for the nation.

good riddance

I like your idea of disappearing his ashes. I hope he is interred somewhere unknown. People forget, and someone, sometime can turn a grave into a shrine in a new cycle of corruption.

I’d say that he would have very few admirers. None that would matter. Too much shame in liking the guy.

Thanks for the great rundown. Loved it!