I can’t remember exactly the first time I heard of Keith Jarrett – some podcast or radio show, and only fairly recently – but the story they were telling caught my attention.

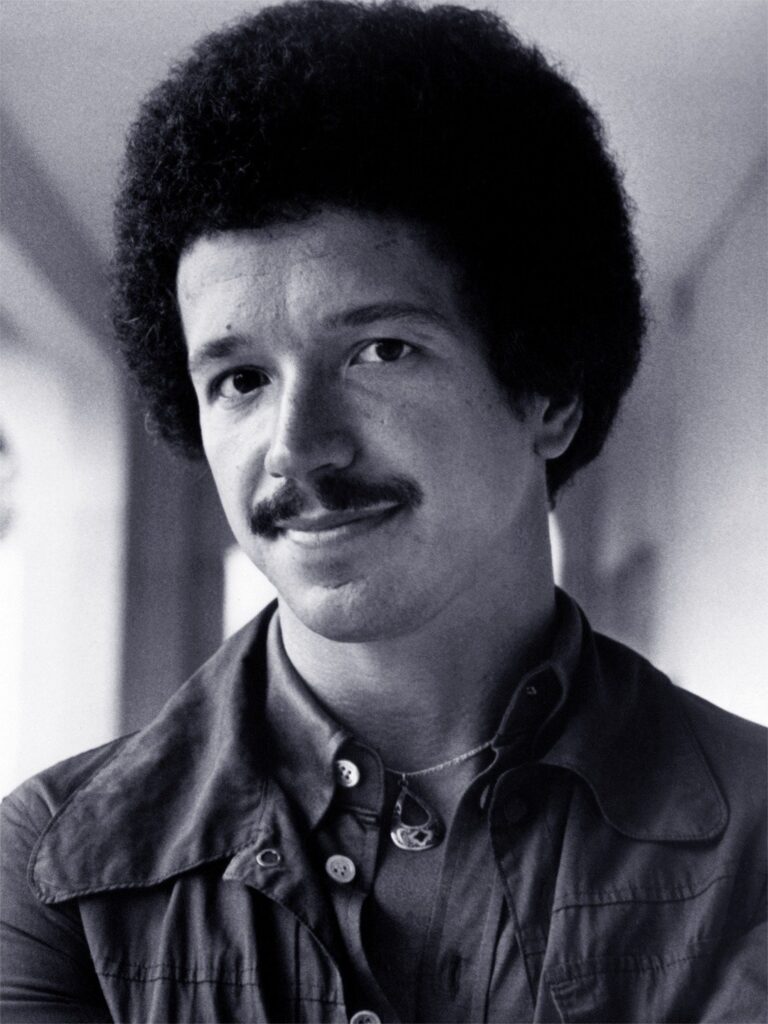

Keith Jarrett is a pianist with a prolific catalogue and an extensive range. His jazz work is smooth — he’s teamed with some of the greats (he played a bit with Miles Davis, and even compromised his normal disdain for electronic music to do so) to produce a sound so sweet and natural you can’t help but be mesmerized. If you dig that kind of music. For me, it’s so relaxing it’ll put me to sleep…in a good way.

Jarrett was a child prodigy on piano, playing for pretty much his entire life (he’s 75 now and stories of his abilities go back to when he was 3). One of his most notable musical attributes is the ability to improvise entire concerts and even more so to treat them as singular occurrences – you’ve got one shot to get this down, and it’ll never happen again. I’m sure that if someone were to ask him to play a piece from one of these concerts, he wouldn’t. In his view, he couldn’t. What he plays is shaped by the very environment in which he plays – the weather, the mood of the crowd, what he had for dinner for all I know – and you could never recreate that environment.

The piece that introduced me to Jarrett was The Köln Concert. It is the story of that concert that I found so fascinating. Jarrett is known for his idiosyncrasies when called upon to play – his desire for utter silence, his dislike of photography — that kind of thing. Patrons of his concerts were sometimes handed cough drops as they entered to prevent any extraneous noises or distractions

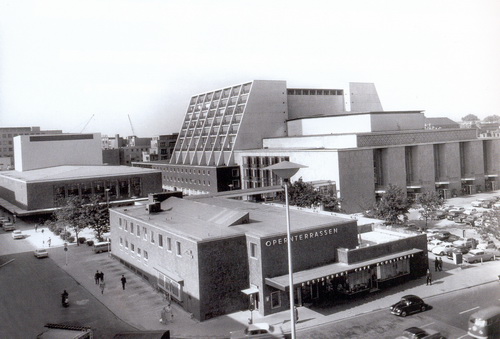

And Köln is rife with distraction. When he arrives for the concert (put together by Germany’s youngest concert promoter, a 17 year-old Vera Brandes) he finds that the grand piano he had requested was unavailable and instead he was being asked to play a baby grand — a rehearsal piano for the hall that was in quite the state of ill repair. Typically, this is something that would have Jarrett walk away…and he nearly did.

But the technician who was going to record the session had already set up the equipment, and oddly, this was enough to convince Jarrett to just go out there and do it.

And there is something then to be said about his very method here. He’s on a piano of questionable quality — more suited for a living room than a sold-out opera house concert. Its bass range is weak and poor, and its higher notes tinny (not to mention pedals that didn’t work). It doesn’t have the guts to fill the room. And Jarrett’s tired. His back hurts. He was only able to wolf down a few bites before performing. It was 11:30 on a rainy night.

And all of that contributed to an incredible performance. Some would say sharper. More distinct as he pounds every key to be heard in the back. More improvisational in how he had to make up for the instrument’s deficiencies. It just had a magic to it. I was so mesmerized by his Köln performance that I bought it and pretty much looped it for a week. I find the first notes of it absolutely haunting. I can’t begin to imagine how someone can take the combination of the adversity and the idea of a few musical notes and then turn it all into this beautiful piece of music.

Now it’s an understatement to say I’m unqualified to go into all (or any, for that matter) of the intricacies that make this work a piece of musical genius. As a matter of fact you’ll find some critics who don’t think it’s all that good, and maybe they’re right. It’s repetitive. It’s simplistic. Or so they tell me. But for some reason it has resonated with enough people to make it the best-selling solo piano performance of all time. It’s got my vote. But part of what gets me there is the story that goes with it.

If you’ve read what I’ve written before, you know I’m a fan of historical context. I believe we make a mistake in judging the characters of history by the standards of another era. This doesn’t mean they were right. It just means that we have to understand what informed the people of that time in order to understand why they did and said the things they did — and perhaps realize we may not have done much differently.

And in something like the Köln concert, I can see a microcosm of this. An unrepeatable moment in time that creates something unique. Not that “you had to be there,” but rather, Keith Jarrett had to be there. On that day. At that time. Under those conditions. All for something like that music to happen. It is an imperfect analogy. Yes, Jarrett cannot recreate the performance. And it took a lot of work for him to even allow it to be transcribed onto the written page so that others could play it (I’ve listened to others, and they’re nowhere near as good – perhaps more evidence in support of the context making the music). But the performance still exists by the good fortune of that recording tech who happened to have been there to set up early enough that Jarrett felt it worth it to play just for the heck of it. And while other moments of history are not timeless – they serve as nothing more than lessons to avoid – the Köln concert is. Yes, musical styles change. They ebb and flow and move throughout history so that there was indeed a time where baroque music, ho-downs, and Devo were the “in” thing (not all at the same time…not that I know of). But they can all be appreciated as “classic” in their own particular ways, and none so much condemned as an aberration to societal norms (although Devo comes close) as some of the events of history.

I feel like Jarrett fits here though. A lesson in the beauty of spontaneity. But also a lesson in the unrepeatable nature of certain contexts. And maybe the lesson here is that we can have a part in that context. We’ve got to grab onto those things that are beautiful – somehow share them in our world and make the lives of those around whom we live more beautiful. And we’ve got to do it while we can.

Unfortunately, Jarrett’s part in that is largely over. I’m writing this now because of a New York Times article I read just this morning. In 2018, Keith Jarrett kind of disappeared from the scene, and now he’s broken his silence to speak of the two strokes he suffered that year. Although he’s made some progress in recovery, he is still partially paralyzed in his left hand. He lives. He can play right-handed if he wanted. And I’m sure the music he could make is still more beautiful than what many others who claim to be musicians could create. But he’s entered a new era, and any music he could make now would fall within that era. Sadly, he no longer feels that he is a pianist, and while many would disagree, this is his call to make. But his body of work is still important and tremendous and, despite the nature of music’s changing landscape, always will be.

And his Köln concert will stand out to me as something that means more than the music. It tells me the importance of moments in time, and it tells me to live them the best we can.